Yet another election with the same promises exposes the state of the politicians, surrounded by non-farmer courtiers who cannot even drum up new slogans.

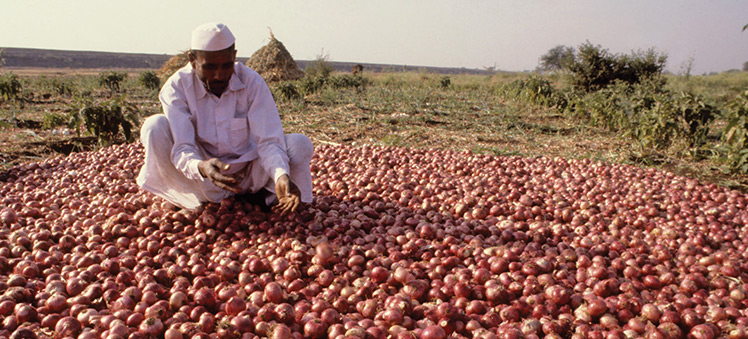

The agrarian core of India, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, is heading for the polls. Poor farmers who have got old hearing the same election promises — of loan waivers, Swaminathan report, higher MSPs and free and cheaper electricity — are getting more of the same. It is sad that politicians are surrounded by courtiers who do not farm and cannot even drum up new slogans.

In this season of election manifestos, there are alternatives that will win elections without saddling tottering state governments with additional financial burden. Let us look at Punjab to understand the situation because this is where environmental and economic nightmares are being rolled into one poisonous brew.

The average Punjab farmer household debt is over ₹5 lakh. Some 10,000 farmers have committed suicide in 10 years of the farmer-oriented state government’s rule, inspite of having assured water, good soil and additionally receiving annual ‘farm support’ of ₹9,000 crore, which mainly includes fertiliser and the power component. Of this, the smallest 34 per cent cultivators receive a measly nine per cent. Farm support is based on use of inputs. Thus the smaller the area that a person cultivates the smaller is the support that the person receives.

In broad brushstrokes, at no extra burden to the exchequer, one can replace the present instrument (favouring large farmers) by direct cash transfer of ₹90,000 each to the a million cultivators, regardless of the size of his holding. In return, farmers will be expected to purchase electricity or fertiliser at market prices. An algorithm could take into account changing prices of fertilisers or power to be reflected in the support amount.

The transferred amount is not income but, if implemented, 70 per cent of the farmers would be net gainers. Delivering social equity through resource distribution is the key to inclusive prosperity. Given that 70 per cent of the farmers are women, transferring the amount directly into the bank account of the lady member of the household will be a clincher. ₹90,000 in the bank account would yield unparalleled political dividends when the average Indian farmer’s income is ₹77,000.

Farmers realising that a ‘rupee saved is rupee earned’ will work towards improving efficiency. They will begin to grow crops like pulses that require lower inputs, leading to the much elusive crop diversification. A cascading effect of judicious use of inputs like fuel, water, fertilisers and, subsequently, pesticides will save depleting aquifers, improve soil health, biodiversity and human health. Think of it as an economic stimulus, whereby WTO worries fade as well. It is absolutely essential that farmers have a choice to use the money as they wish.

However, after the dream merchants are elected to office, they invariably renege on promises. Prodded by government promises of higher moong MSP (₹5,225) farmers sowed over 32 lakh hectares of moong but the promised purchase did not materialise. The price is expected to continue to fall below ₹3,500 and each small farmer could lose about ₹25,000. The total presumptive loss to just the moong farmers for this season alone could be ₹5,000 crore.

When it comes to farmers, political parties have a narrow two-fold agenda to win elections. They comprise dishing out populist promises and blaming others. This is best explained in Ambrose Bierce’s words: “Politics is a strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles.”